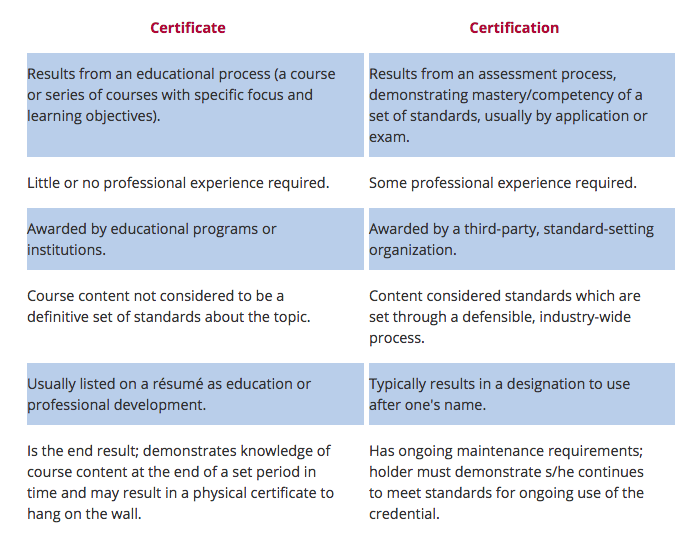

I found this so fascinating: the International Rescue Committee has a new guide for service providers, Myths Surrounding Virginity. I just finished working my way through it; what a great resource for really sifting through the issues related to the subject. I can see using it for educating other disciplines on the realities of what we already know as forensic clinicians (and probably a few folks within healthcare, as well). It’s brief, so I encourage you to download it (PDF) and check it out for yourself.

From the website:

Virginity is a sensitive subject. The concept itself has a complicated history and, while it describes sexual activity for all genders, there is greater value placed on female virginity. For women and girls, virginity is too often tied to moral character, purity, honor, and social, moral and religious values.

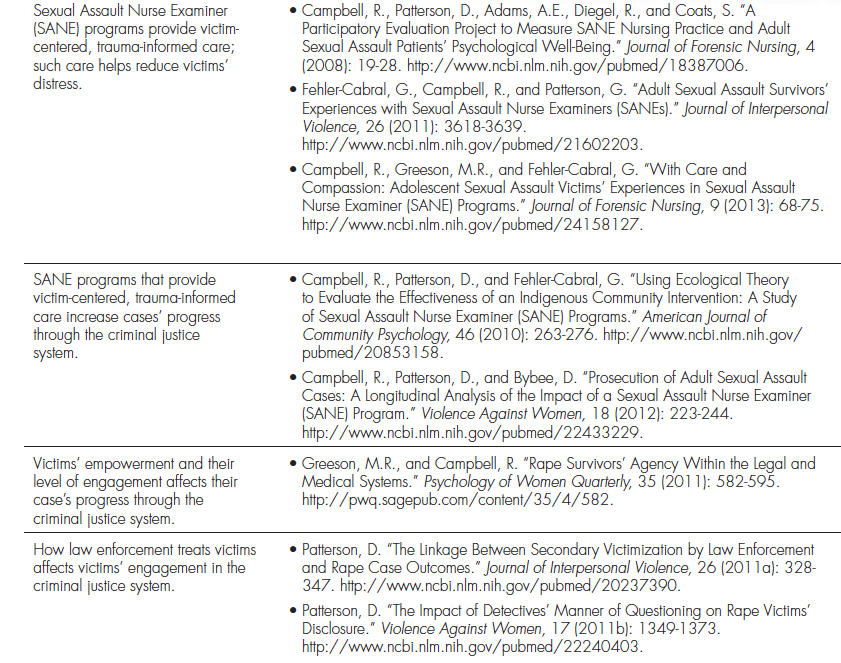

In following the endnotes in this document, I was reminded of a piece I had posted a while back. You may want to also revisit it, while you’re focused on the subject matter. See also this free full-text article (PDF) on virginity testing (as well as this one); this expert statement on the issue of testing (abstract only); and ethics statements here and here.

Our first offering in the FHO store, Injury Following Consensual Sex is now available. If you haven’t ordered a copy yet, you can find it here.